What is FSVP and how will it affect me?

Before I started to write the world’s best blog post on Foreign Supplier Verification Programs (FSVP), I made the prerequisite cup of coffee and spread out pages of handwritten notes, several printed articles and legal opinion papers on the subject.

The first 4 or 5 rough drafts I created were quickly deleted as I was having difficulty trying to find an innovative way to “tell the story” because it has already been done to death. Article upon article, blog upon blog, overview upon overview… they were all simply rehashing the same bullet points and I was following suit.

I couldn’t help but wonder how anyone could be unfamiliar with the contents of FSVP when there is so much information in bullet point form available at Google University? Yet, I speak to food manufacturers on a routine basis who still have questions.

For me to understand what’s truly needed I’m going to need to put my old QA Manager’s hat on, and I’m also going to need another cup of coffee.

The goal of the FSVP is to ensure that each food imported into the US has the same level of public health protection as required under the preventive controls and produce safety regulations. This means the food is not adulterated or misbranded with respect to allergen labeling.

The cost of not adhering to this is significant as the FDA is now equipped to take regulatory action against importers that fail to provide necessary assurance for food safety. The FSVP (and by extension FSMA) has given the FDA new muscles to flex in the fight for food safety and it would be poor judgment to think they won’t exercise that privilege.

FSVP and FSMA have given the FDA new muscles to flex in the fight for food safety

At this point in many blogs, the usual pontification ensues covering these basic elements of FSVP (Warning: bullet points ahead!):

- Hazard Analysis

- Evaluation of Food Risk and Supplier Performance

- Supplier Verification

- Corrective Actions

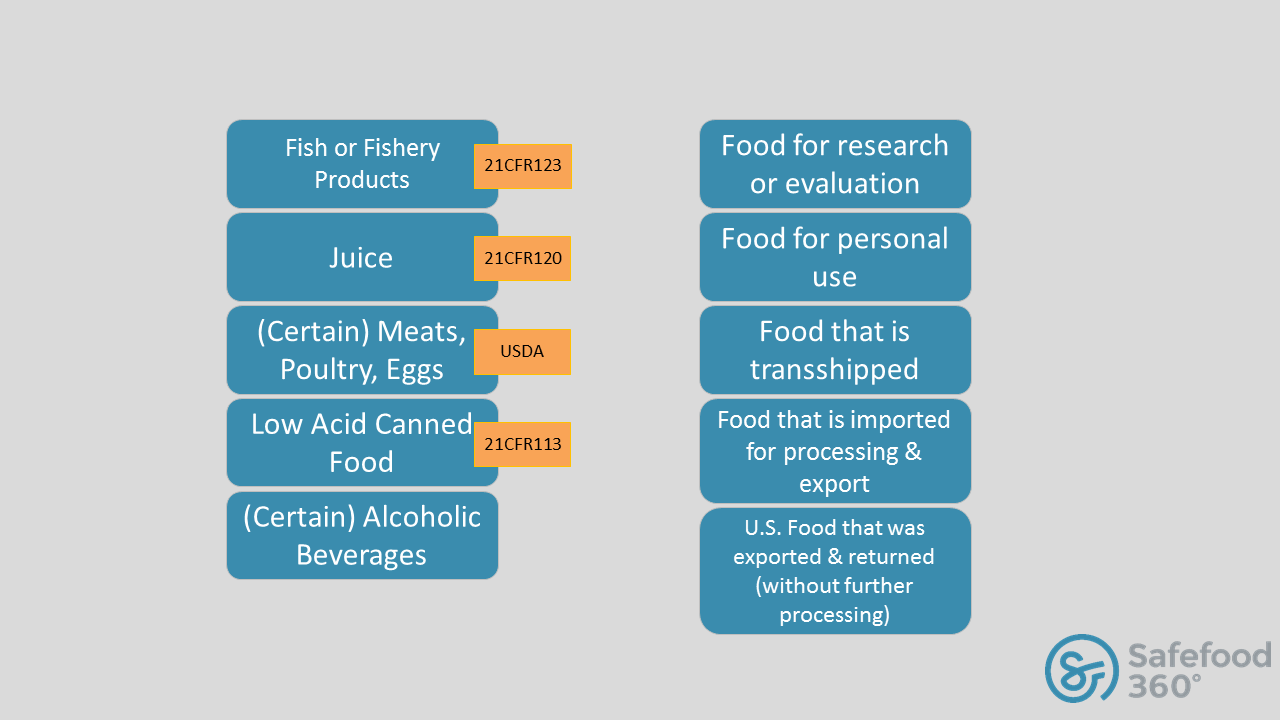

But what you really want to know is “does FSVP affect me”? Well luckily the FDA has developed a decision tree which answers that question you can see here. But for the purposes of this blog, let’s just look at at the import categories that have certain exemptions from FSVP rules:

For the rest of you, if you thought that supplier management was a cumbersome or difficult task in the past you might resent not choosing a career in something simple like nuclear physics as the FSVP final rule reads a bit like a complex assembly instruction manual for the Space Shuttle.

May 2017 will be the first round of compliance inspections, but it goes without saying that you shouldn’t wait until then to get your programs ready.

What do I do now?

By now you likely have familiarized yourself with the final rule and may have developed a road map to compliance. If you haven’t then it’s time to sit down and re-evaluate your programs to ensure you are ready for the change.

The first thing to do is determine whether the FSVP applies to you, and if so perhaps you’ve already started making your plans. I’ve talked with many companies who are considering creating an entirely new position for a FSVP “expert” to help them navigate their way to compliance.

This might seem like overkill, but the more you dig into the final rule the more you will realize that there might be some merit to beefing up your staff.

Many companies are considering creating FSVP “expert” roles … it might seem like overkill … but there is merit to beefing up your staff

After all, somebody is going to need to keep track of everything. The FSVP isn’t asking for broad brush strokes. To quote the FDA, the importer must “perform a hazard analysis that includes identifying known or reasonably foreseeable hazards associated for each imported food or type of food and determining whether they require a control.”

Your developed “FSVP Program” should include provisions to use a qualified individual to develop and perform FSVP activities. (Warning: more bullet points!)

- Perform a Hazard Analysis (that includes identifying known or reasonable foreseeable hazards associated for each imported food or type of food and determining whether they require a control)

- Evaluate risks posed by the food

- Evaluate the performance of the foreign supplier

- Conduct appropriate supplier verification activities to provide assurance that the hazards requiring a control in the food you import have been significantly minimized or prevented

- Annual onsite auditors

- Sampling and testing of food

- Review relevant food safety records

- Other appropriate activities

- Take corrective actions

- Investigate the adequacy of the FSVP

- Re-evaluate the food and foreign supplier every three years (or sooner if new hazards are identified or if the foreign supplier’s performance necessitates more frequent evaluation)

- Identify the FSVP importer when filing for entry with U.S. Customs and Border Protection

- FSVP importer’s name

- Email address

- Unique facility identifier recognized as acceptable to FDA

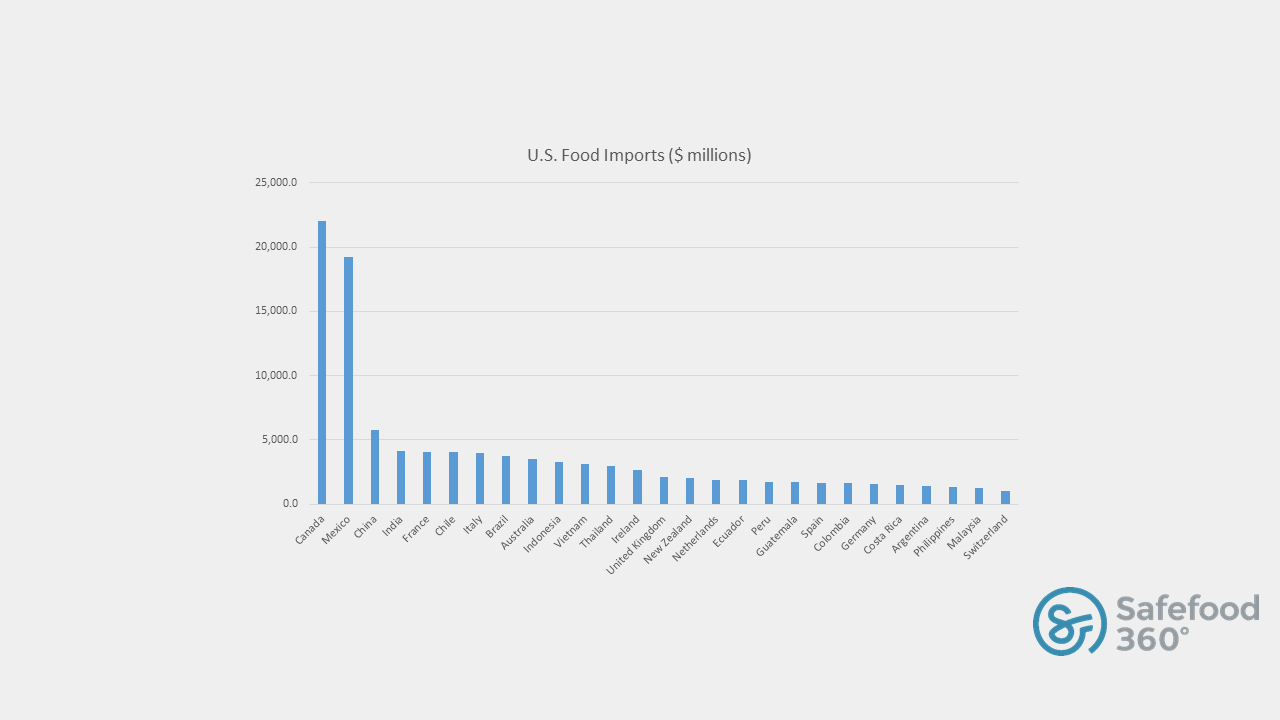

US Food Imports by Country (Source: USDA Economic Research Service)

If you’re still trying to figure out if FSVP applies to you, try looking at your procurement department. If you haven’t been paying attention you might be surprised at what you find out! Roughly 20% of the food used in the US is imported each year. Even if FSVP will not affect you there is a high degree of probability that it will affect others in your industry.

What is the future of FSVP?

While some companies are considering the addition of one or two more individuals to help carry the load, others are looking to invest in software that will make the task easier while allowing them to have increased visibility into their entire Food Safety Management program.

The food safety experts here at Safefood 360° have been incredibly busy dissecting FSMA and integrating the changes into the software, so our clients know that Safefood 360° has the solution they need. If you would like to learn more about our FSMA solution or see it in action click here.

As for me? Brazil and Colombia are on that chart which reminds me, I’m going to need another cup of coffee.

Disclaimer: This blog is not legal advice and should be considered educational in nature. You may implement this advice at your own risk.

Great article.

Thank you! I’m glad you enjoyed reading it.

Excellent blog, enjoyed the humour as well as the information.

Hi Denis,

I agree. We always enjoy Chris’ blend of great insight and trademark humour as well. Check back in with us next week as he has another excellent one coming up on FSMA which I’m sure you’ll enjoy.

I believe you are incorrect regarding fsvp not affecting seafood importers. Seafood related plants are exempt from having to create a HARPC plan because the FDA regulates their HACCP plans. However regarding other programs falling under the FSMA regulations such as FSVP, sanitary transport, having a PCQI, they must comply fully. I fear you may be misleading seafood processors/distributors into not being fully compliant.

Hi Lisa,

Thank you for your feedback. We’ve edited the blog to remove a bit of ambiguity and ensure the reader understands that the FSVP exemptions are applicable to specific categories of food which are being imported.

You are very correct in stating that seafood related plants must fully comply with the FSMA final rules which are appropriate to them. With that said, it is important to understand that the exemptions mentioned in this blog (and the FDA decision tree which this blog links to) are not referring to a carte blanch exemption to the industry in whole, but only to the parts which are legally exempted. For instance, if a company imports fish or fishery products which are regulated under and compliant with 21CFR123, the FSVP would not apply in that instance. However, that same company might import olive oil. The olive oil would be subject to the requirements under the FSVP.

Having said that, Lisa, we have edited the blog to indicate the exemptions applying to specific import categories. Also, further in the blog please note that it is clearly indicated that compliance to the FSVP is not going to happen through the use of ‘broad brush strokes’, and the FDA is directly quoted stating that the importer must perform a hazard analysis on each imported food or type of food to determine whether they require a control. This is a very complex rule, so it is very important that assumptions not be made in lieu of understanding that the onus ultimately lies upon the importer to ensure whether the FSVP requirements will apply circumstantially or not.

Thank you again for your feedback and for pointing out the potential lack of clarity which we have addressed.

Kind regards,

Chris