Food Safety – Falling Between the Cracks

There appears to be an emerging issue regarding the true nature of what I usually term the Food Safety Framework which governs food business operators in many geographic locations globally. In times past, the framework was so much simpler. The businesses proprietor driven by local regulation where it existed was responsible for safe food production.

Over recent decades, food safety outbreaks, zoonotic scares, increasing dominance of retailer brands and globalization have made for an increasingly complex food supply chain and compliance structure. Within this the legal, commercial and private compliance lines have begun to blur somewhat.

The Food Safety Framework

From the perspective of the food producers, processor and manufacturers the food safety framework has become an increasingly complex entity. The number of legal, commercial and private standards a business now needs to comply with to conduct business at sufficient scale and maintain viability and profitability is increasing and ever changing.

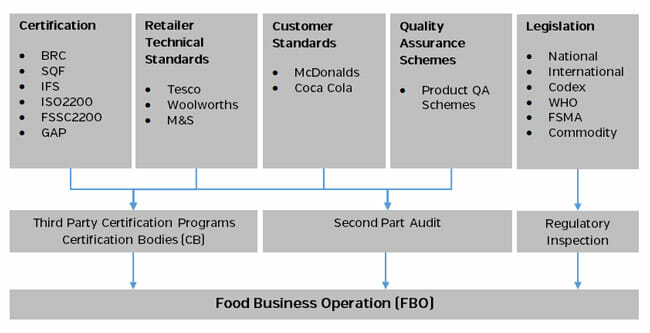

This framework can be summarized in the following graphic:

A food business operator (FBO) may be subject to some or all of the above elements of the food safety framework. Looking closer at the framework we can see the complexity and drivers of these requirements.

Certification: We have recently seen an explosion of certification of food safety systems conduct by independent third party certification companies under one or more certification schemes. The Global Food Safety Initiative (GFSI) in particular has stimulated this growth and within this there is now significant competition between various schemes and CB’s for a slice of a growing global market.

Retailer Technical Standards: Despite the original objectives of the GFSI to harmonize and standardize best practice in food safety management, many retailers have maintained and continued to develop their own technical standards for suppliers. These technical standards build on the requirements of the GFSI providing more prescriptive requirements to comply with general requirements. These standards are very valuable and require significant commitment by a FBO to meet the standard.

Customer Standards: These standards can vary in terms of prescriptive requirements but can be operated by organisations who maintain valuable brands and seek direct assessment over their key suppliers.

Quality Assurance Schemes: Again these can vary widely and include quality assurance schemes which are usually commodity and product based e.g. meat, produce etc. They are usually operated by trade organisations or national marketing agencies.

Legislation: Traditionally national and international regulations set out the minimum standard of compliance for a FBO but following the BSE crises and the introduction of FSMA in the USA this has changed with more prescribed and tougher regulations making the requirement more challenging particularly for smaller, less resourced businesses. Enforcement is through a massive program of regulatory inspections.

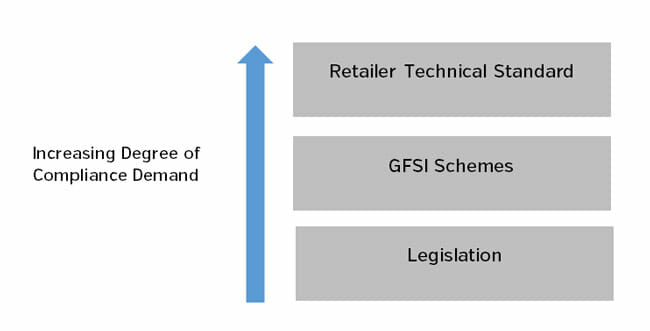

In terms of technical and compliance demands the framework can be summarised as follows:

As we can see, a single food business operator can be subject to quite a complex framework of compliance requirements from a number of interested stake holders with varying objectives, agendas and sophistication. With so much auditing, inspection and assessment now common place in the sector it is important that the industry as a whole now takes time to reflect on the nature of how the safety and efficacy of food is assured in the modern supply chain and where responsibility starts and finishes for the relevant parties.

Finger of Blame vs. Collective Responsibility

I know from working in the food industry for two decades in a variety of roles that assuring the safety of food is not an easy task. Even with the best of resources, intentions and goodwill, food processors, auditors, regulatory agencies and retailers can become unstuck by food safety events. It is an unfortunate reality that the food safety hazards we seek to eliminate or reduce care little for our ever increasing efforts at regulation, monitoring, certification and collaboration.

However, as we know, this is not the full story. Recent events such as Horsegate demonstrate that where there is clear intent to disrupt the integrity of our food supply there are significant barriers to preventing it. Horsegate and more recent outbreaks and subsequent criminal and legal suits show us that the legal responsibility for food safety can be passed up and down the supply chain leaving the consumer in an arguably weakened position.

Now let’s frame this issue more clearly. The food sector and the resultant food we consume has never been subject to more scrutiny, audit, monitoring and inspection than in the history of modern food processing and preservation. Why is it then that the global industry continues to produce food safety issues of global scale – outbreaks in USA and Germany, Horsegate and dioxin contamination. What is clear is that a large volume of audits and inspections will not in and off themselves prevent the very issues we are trying to avoid.

This is not to say that audits and certification are worthless. The opposite is the reality. But alone they are not sufficient. Have we built a lofty skyscraper of compliance on a bed of sand? I don’t believe so but there are cracks and I fear we are in danger of simply plastering over them.

To the already complex arrangement for FBO’s we are now adding new risk assessment and control models for food fraud, food defense, vulnerability assessments (VA) and so on. Is this reaction justified and does it address the true nature of the issue? As it stands, the heads of many food safety managers on the ground must surely be spinning. The heads of those engaged in auditing and inspection must also be spinning.

Missing Elements

So what are the missing elements? I won’t pretend I have all the answers. I don’t. But I believe we need to start asking these questions and start filling in the gaps. Food safety ultimately comes down to the guys on the ground who make those critical judgements and decisions on sourcing, processing, packaging and distribution. And we are not creating a clear framework and environment for them to effectively manage food safety. We are simply adding to an already complex framework which is losing integrity and showing cracks despite our collective best efforts.

There are certain things I believe we can do as part of a global strategy including:

- Alignment of food safety goals at the regulatory, commercial and private level. In other words getting back to the spirit and vision of the early days of the GFSI. This will require bringing together national and international governmental agencies, retailers, influential large food businesses and private schemes to build a common, robust and less complicated framework.

- Development of a genuine food safety profession designed to equip our managers, auditors, inspectors and policy makers for the challenges ahead. This will require the widespread development of specific food safety programs at both under-graduate and graduate level with clear career paths.

- Development of more integrated Hazard Analysis, Risk Assessment and Risk Management models at processing level which halts and reverses the proliferation of models in reaction to current events. This should include the root and branch review of the existing HACCP model which no longer meets the new world of food safety.

- Make the global supply chain smaller through the application of new Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) allowing for transparency, vertical and horizontal integration of supply chain data and timely alerts and actions. This will need to include Cloud technologies.

I have no doubt I will return to these points in future blogs but for now I think we need to open up the obvious issues in our personal, practical and academic pursuit for a better understanding. From there we can create effective solutions.

About the author

George Howlett is the CEO of Safefood 360° and one of Europe’s leading food safety experts. Before establishing Safefood 360° he worked at some of Ireland’s most prominent companies and brings the expertise with him. George also lectures in the MSc for Food Safety Management in the Dublin Institute of Technology.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!